In order scale services with tight latency (and throughput) requirements, distributed systems programmers are forced to accept stale or inconsistent data. Typically this means using an eventually consistent data store like DynamoDB, MongoDB, or Riak. With this weaker consistency model, it's hard to know when writes will become visible to others, or what state of the world you're going to get when you read.

If you're implementing a service like Twitter, the prevailing assumption seems to be that you don't have to worry unduly about pesky consistency issues because the service is assumed to be best-effort anyway. Besides, nothing is every really too far out of date, at least for the average case.

However, eventual consistency means views of highly contended data items might be significantly more stale than others — how old is too old? Or even if you're implementing one of these “softer” social network applications, some guarantees must not be violated. If a concurrency bug results in a security violation, such as a tweet showing up in a timeline it shouldn't, then it could be a big problem. But there are fundamental limits to scaling strong consistency, so we can't just give up weak consistency completely. So what are we to do?

If there was a way to express exactly what errors were acceptable in the application, then maybe we could ensure that those were not violated, and we just might still have enough slack to be able to give the scalability and performance we desire.

I'm proposing to help programmers deal with inconsistency in disciplined ways, using type systems and runtime support to let them explicitly trade off correctness for performance and scalability where their application can tolerate it, while ensuring the rest of the application remains correct.

There's a whole lot to talk about with regards to how this programming model might work, or how to implement it within high-performance data stores. But first we need to clear up what we might mean by error tolerance because it turns out we might be thinking of different things.

Example: Twitter (again)

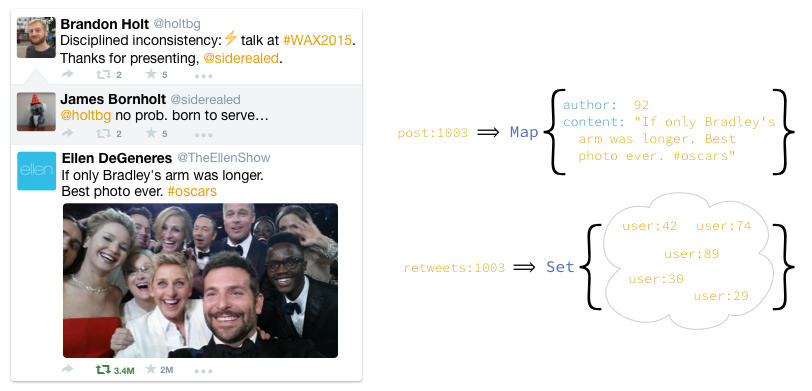

If you've heard me speak at all in the last, hmm, half a year at least, then you've probably heard me use this example, but just in case, I'll review it quickly here. Retwis is a Twitter clone built on Redis using its support for data structures. This is great because it means instead of using just keys and values, we can work with data structures like lists and sets. For this example, all that's important is that we keep track of all the users who have retweeted a post with a Set.

To retweet the post, users add themselves to the set.

def retweet(post, user)

# ...

Set("retweets:#{post}").add(user)

# ...

endWhen loading a timeline, we check the size of the set in order to display the number of times each post has been retweeted (we won't load the full list unless the user clicks on it).

def view_post(post)

nretweets = Set("retweets:#{post}").size()

# ...

endThe problem with this is that while anyone is retweeting a post, we can't get a consistent retweet count because the retweet set is in the process of changing. For many tweets this is no problem — retweeting just takes a fraction of a second, so we can just wait and get the final retweet count.

Ellen Degeneres's selfie above made history at the 2014 Oscars by being the most-retweeted tweet ever. During the hour after it was first posted it was retweeted over 1 million times. Given our retweet model, finding a time to read a consistent size of the retweet set is going to be difficult. Because of this, what will actually happen is they'll read a somewhat stale count that's weakly consistent and accounts for some fraction of the concurrent retweets.

The answer we'll get back is probably reasonably close, but it could vary moment by moment as more or fewer people retweet the post. For any given retweet count, we have no idea how far from correct it is.

Error Tolerance

Wouldn't it be nice to have some idea what the error is? Rather than simply accepting that it could be arbitrarily wrong but probably won't be, what if we could ensure that the error fit within some acceptable range? What if we could tailor this error tolerance based on exactly how we use the value. For instance, in Twitter, we have a pretty well-defined notion of what is acceptable: what is displayed to the user.

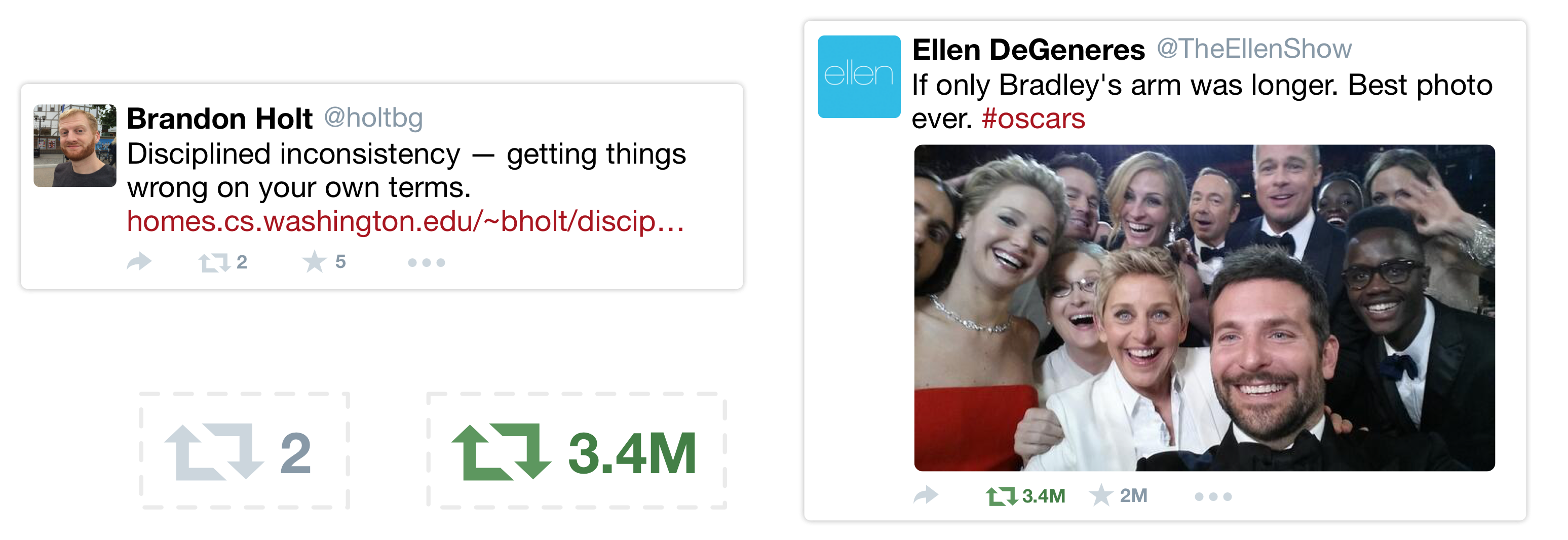

For tweets like Ellen's Oscar selfie, we truncate it to a couple significant figures, so the count can be off by hundreds of thousands and still come out the same. Meanwhile my tweet, which has been retweeted 2 times (a lot for me), better have exactly the right answer otherwise I'll know (because one of them is probably my mother, who called to tell me she retweeted it).

This is the crux of what I've started calling disciplined inconsistency: the programming model should express what errors are tolerable for a given application. But this is where there are two ways to slice it.

Bounded error

One of the ways I've been thinking about bounding inconsistency is by having programmers express error tolerances. For instance above, you could say the size() operation must be within 5% of the correct answer: size<0.05>() . Then my assumption is that the system will ensure that this is the case, by either aborting the transaction containing my size<0.05> operation, or by preventing other add operations that would cause it to diverge too much. I would call this bounded error.

Error bounds

However, I was talking to Allen Clement at EuroSys last week, and he gave me a different perspective. To him, the primary concern is getting an answer, any answer, either as fast as possible, or within a certain amount of time. A desire for high availability and low latency is why many use eventual consistency.

Bounded error flies in the face of that because enforcing it could delay some answers too long. What someone like Allen might instead prefer to do is to set a latency bound, where the data store tries to hold on as long as possible to give the most correct answer, but in the end returns something it knows is incorrect. In the case of these latency-bound operations, can we still deal with inconsistency in a disciplined way?

Yes we can!

We can represent the error bound as part of the result of the operation!

The set of possible values is determined by the type of inconsistency or approximation use, so the way we represent the error bound or value distribution will vary. In the case of a racy size, we can return the interval of possible sizes based on all the adds that were in flight when the size was read, which we could use to display the most accurate count possible to the user:

On the other hand, the size could come from a HyperLogLog, which keeps track of the approximate number of unique elements probabilistically. Or it could just be a stale snapshot read.

These ideas took shape during chats with my labmate James, first author on Uncertain<T>. In that work, rather than returning a single result from something with known uncertainty (such as a GPS sensor), operations can return results as a probability distribution over possible values. Exposing the distribution to the program allows it to make decisions based on likelihoods, such as a warning when a value is outside a given range with high confidence. It seems like a similar type system could help distributed systems programmers reason about uncertainty resulting from weak consistency.

Disciplined Inconsistency

There is a lot of uncertainty in the distributed systems space resulting from various weak consistency models. Using types we can let programmers reason about this inconsistency in a disciplined way, expressing how to handle uncertainty and how much the application can tolerate. When paired with a data store that is capable of tracking and bounding inconsistency, this will allow programmers to make tradeoffs between accuracy and scalability.

The programming model for disciplined inconsistency is still very unclear. So far we have at least discovered that our mechanisms should respect the two ways of looking at error tolerance:

- Bounded error: ensure result satisfies certain criteria, blocking or aborting otherwise.

- Result uncertainty: result encodes the set or distribution over potential values, letting the programmer decide what action to take.

I have many questions remaining, including:

- How can bounded error be enforced for replicated data types?

- What is the overhead of measuring this uncertainty and is it low enough to tolerate?

- In what ways can we approximate to increase performance or scalability?

- Is this useful to programmers? Will they know where they can tolerate error?

- Most importantly: what will the clever, multi-layered name be for this system?

I will be beginning to answer some of these questions by implementing and evaluating them. Others will require more brainstorming and literature review. But I would love to hear from you if you have thoughts about any of them, so please reach out to me on Twitter!

Disciplined inconsistency: getting distributed systems wrong — on your own terms. http://t.co/fFvg3zlJ3P

— Brandon Holt (@holtbg) May 4, 2015